BAD KREYÒL: A DEEPER DIVE

The Kreyòl Language

Prior to colonization by Europe, the primary language of Haiti, or Ayiti, was Taino, spoken by the indigenous people of the land. In fact, Ayiti is an original Taino word meaning “land of mountains”. In the 1600 and 1700s, Haitian Kreyòl (anglicized as Creole) developed as a “contact language” between enslaved Africans, gens de couleur libres (free people of color), and the French colonists. While Haitian Kreyòl has roots in French, and there is overlap in pronunciation and sometimes in meaning, it is its own language. Kreyòl is a revolutionary language that united the enslaved Africans in fighting for, and ultimately winning, their independence from the French. Similar classifications of Creole are also spoken in Louisiana and Saint Lucia.

Kreyòl terms featured in the play:

Ou fou = Are you crazy?

Fanmi = Family

Lougawou = Shapeshifter

Enbesil = Imbecile, dummy

Ban m zòrèy mwen pitit! = Stop talking! (or, more literally, give me my ears!)

Konprann = Understand

Zanmi m = My friend

Sa w ap gade la = What are you looking at?

Dyaspora = Diaspora, used to mean a person of Haitian descent who lives in another country

Ki jan ou rele? = What’s your name?

Haitian Organizations and Rights Groups

Haiti Outreach Mission

The Haiti Outreach Mission is dedicated to serving the city and surrounding communities, especially the children, of Mirebalais, Haiti (in the rural mountain area about 35 miles northeast of Port-au-Prince). They provide mission trips with a team of doctors to set up free medical and health clinics, and provide support for schools. Dr. Dominique Monde-Matthews is the founder, and a family friend of Dominique Morisseau. On her trip to write this play, Dominique (along with Co-Sound Designer and husband Jimmy Keys, and her brother Frantz PR Morisseau) accompanied her father Frantz Morisseau in Mirebalais where he served as a Translator for the Free Health Clinics.

To donate to the Haiti Outreach Mission and support their valuable work, visit their website.

Kouraj

Kouraj Pou Pwoteje Dwa Moun, (Courage to Protect Human Rights) or Kouraj, is a Haitian non-profit aimed at combating discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Started in 2011, the organization offers advocacy and legal support for the ‘M Community’ (an umbrella term for LGBTQ Haitians), as well as health services and anti-discrimination training.

“For me, pride means being homosexual and living my identity to the fullest.” – Méus Stephenson, KOURAJ Executive Director

To learn more about Kouraj, read this Global Pride Spotlight.

SeroVie

SeroVie is a Haitian organization that provides free reproductive and sexual healthcare for gay men, sex workers, victims of violence and more. The organization supports the prevention and management of infectious diseases, and offers free condoms, STI and HIV testing, and other specialized clinical services.

To learn more about SeroVie, visit their website.

Restavek Freedom

Restavek Freedom was founded to advocate for restaveks, or children from rural families sent to cities to live with host families and work as domestic help. Many restavek children are overworked and not offered the opportunity to go to school, and in some instances, are abused by their host families. Staff from Restavek Freedom frequently check in with the children, their parents, and their host families, fund the children’s educations, and in extreme circumstances, remove children from unsafe environments.

To donate to Restavek Freedom, and support their work, visit their website.

Haitian Network Group of Detroit

The Haitian Network Group of Detroit is a non-profit dedicated to promoting Haitian culture and welfare, with a focus on giving Haitians living in Detroit the opportunity to connect with each other. The organization also offers services and support for recent migrants, including hosting resource fairs and offering translation services.

To support the organization by donating, volunteering, or becoming a member, visit their website!

Dominique’s Inspiration List for Bad Kreyòl:

– Filmmaker Raoul Peck’s documentary film, Fatal Assistance

– Author Edwidge Danticat’s novels, Breath, Eyes, Memory and The Dew Breaker

– Musician Wyclef Jean’s song, “Yele”

– Author and Historian CLR James’ book, The Black Jacobins

– Randall Robinson’s memoir, Quitting America

(Photo by Dominique Morisseau)

A Timeline of Haitian History

Pre-1492

Haiti is originally home to the Taino, a population indigenous to the Caribbean.

1492: Arrival of the Europeans

Christopher Columbus lands in Haiti. He names the island Hispanio. Soon after, the Taino are forced into slavery, and the combination of infectious diseases and terrible working conditions cause the population to dwindle.

1517: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Begins

Europeans begin to bring over enslaved people from Africa to work the plantations and gold mines.

1697: The Spanish Cede Haiti

Haiti becomes a French colony.

1791: The Haitian Revolution

By the late 1700s, the estimated population of Haiti is roughly 556,000, including 500,000 enslaved Africans, 32,000 European colonists, and 24,000 free individuals of multiracial descent. In 1791, the Haitian Revolution begins with a rebellion by the enslaved Haitian workers. As a peace offering, free Haitians are offered French citizenship, but this does little to quell the revolt.

1801

General Toussaint Louverture declares himself governor-general of Haiti and abolishes slavery on the island. Louverture leads the revolt against the French and Spanish.

General Toussaint Louverture (Credit: NYPL)

1803

The Armée Indigene defeats the French at the Battle of Vertières, led to victory by freedom fighters Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe.

1804: The First Black Republic

On January 1, 1804, Haiti is declared independent, making it the first and only country founded by formerly enslaved people, and the first Black independence in the history of the world.

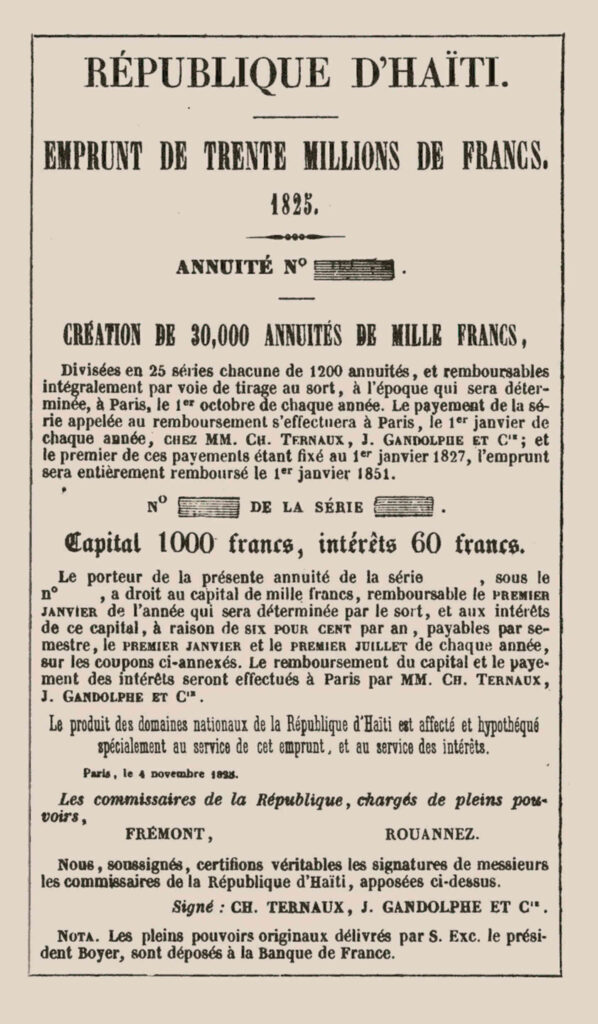

1825: The Continued Exploitation of Haiti

Haitian leaders initially propose paying the French government 15 million USD in order to recognize the country’s independence, the same amount the United States had paid for the Louisiana Purchase. The French refuse, and counter with a demand of 150 million francs. They then enforce this demand with the threatening presence of warships in Haiti’s harbors. Haitians are expected to pay reparations to their former slavers and their descendants. The French also force the newly formed Haitian government to take out a loan to make the first payment, putting them in “double debt.”

“Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black or forgiven the Almighty for making her black.” – Frederick Douglass, 1893

Rendering of the 1825 loan from France by Le Pelletier de Saint Remy

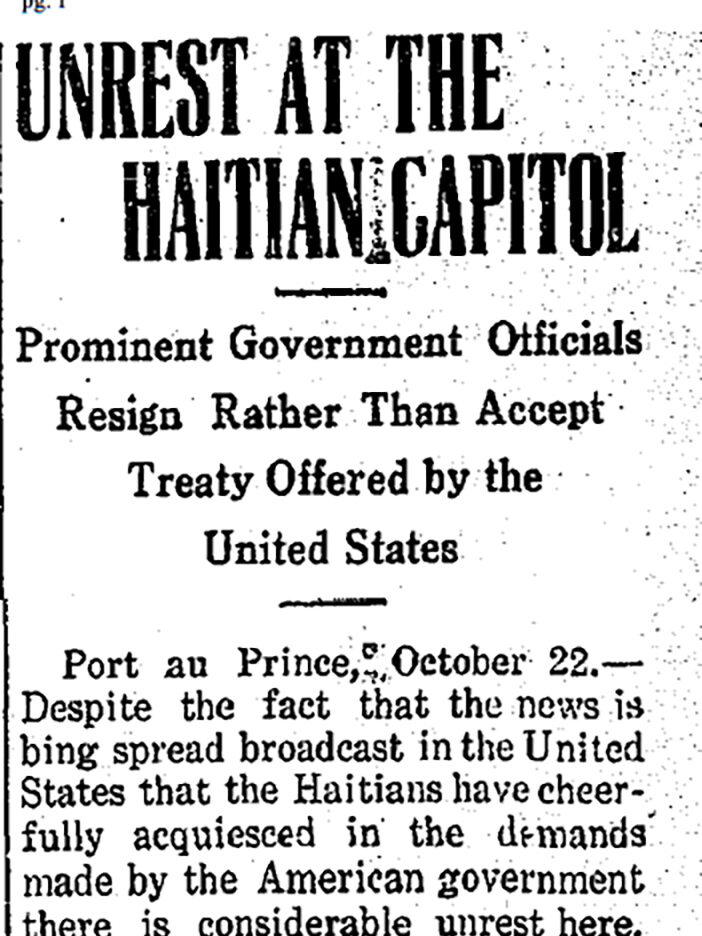

1915: The United States Invades

Seeking to use Haiti as a Naval base, the U.S. invades the country. The U.S. next begins to shift over Haiti’s financial reserves to their own systems.

Headline from the Baltimore Afro-American, October 30, 1915

1934: Occupation Ends

The U.S. troops officially pull out of Haiti, but continue to hold power over Haiti’s finances until the late 1940’s.

1945

The Haitian President, Elie Lescot is granted the powers of a dictator by his congress, backed by the United States.

1946: Overthrowing Lescot

A student journal, La Ruche, publishes a paper declaring the year for the victory of democracy over “fascist oppression,” and calling for freedom of press. Théodore Baker, (uncle of Dominique Morisseau) is one of the editors of La Ruche. Mass protesting ensues and leads to the resignation of the Lescot regime.

Dominique Morisseau’s uncle (4th from the left), and the editors of La Ruche

Check out La Ruche at the link below:

https://ile-en-ile.org/gerald-bloncourt-les-cinq-glorieuses-de-janvier-1946/

1947

Haiti finishes paying off the money owed to France.

1957-1986: The Duvalier Dynasty

François Duvalier (referred to as “Papa Doc”) enforces an autocratic dictatorship over Haiti. He then declares himself ‘President for life,’ and establishes a Presidential Guard and the Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale (commonly referred to as Tonton Macoute) who serve as secret police. The senior Duvalier’s dictatorship was marked by corruption, health crises, and death. This continued after his death in 1971, when Jean-Claude Duvalier took over.

Papa Doc and Baby Doc

1971: The Death of Papa Doc

After Papa Doc’s death, Baby Doc takes over ruling the country.

1984 – 1986: Anti-Duvalier Protest Movement

Protests break out in 1984 in the city of Gonaives after law enforcement beat a pregnant woman, and in November of 1985, protests are held in cities around the country. In January 1986, Baby Doc’s opposition calls for “operation uproot,” or a general strike, and Catholic church officials denounce his rule. Finally, on February 7, 1986, Baby Doc flees to France.

Headline from The New York Times, 1986

1991: Jean-Bertrand Aristide and the Coup

Jean-Bertrand Aristide is elected president, becoming Haiti’s 1st democratically elected leader. However, Aristide is ousted in a military coup later in the same year. Aristide goes on to be president two more times, in 1994-1996 and 2001- 2004.

Headline from The New York Times, 1995

2004: A Second Coup for Aristide

Aristide is ousted from office a second time in another military coup. Many believe the U.S. orchestrated this coup.

Headline from The New York Times, 2004

2010: The Earthquake

On January 12th, 2010, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake hits Haiti, causing extreme damage throughout the country. The earthquake causes 300,000 deaths, and displaces more than a million people. It is estimated that more than 300,000 homes collapsed, and 60% of Haiti’s administrative and economic infrastructure, 80% of schools, and 50% of hospitals were destroyed.

Map showing the 2010 earthquake’s spread

Currently

A culmination of years of political instability, including the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in 2021 and the resignation Prime Minister Ariel Henry in 2024 – violence, food insecurity, and displacement are at an alarming high, especially concentrated in Haiti’s capital Port-Au-Prince.

Accompanying Image:

Headline from The Guardian, 2024

Edwidge Danticat On Haiti and Hope

“I have hope, I say, because I grew up with elders, both in Haiti and here in the U.S., who often told us, “Depi gen souf gen espwa”—as long as there’s breath, there’s hope. […] Besides, how can we give in to despair with eleven million people’s lives in the balance? Better yet, how can we reignite that communal grit and resolve that inspired us to defeat the world’s greatest armies and then pin to our flag the motto “L’union fait la force”? Unity is strength.”

-Edwidge Danticat, The Haiti That Still Dreams’ (The New Yorker, 2024)

Edwidge Danticat is the award-winning Haitian author of Brother, I’m Dying, Krik? Krak!, The Farming of Bones, and more. Read her full essay for The New Yorker here.

References and Further Reading

Global Pride Spotlight: KOURAJ

Haitian Network Group of Detroit

The Haitian Revolution – Encyclopedia Britannica

“The Greatest Heist in History” – Marlene Daut, The Conversation

The Root of Haiti’s Misery -The New York Times

Haiti’s Lost Billions – The New York Times

The Haiti That Still Dreams – Edwidge Dandicat, The New Yorker

Freedom in the Black Diaspora: A Resource Guide for Ayiti Reimagined

Haitians overthrow regime, 1984-1986 – Global Nonviolent Action Database

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake

The Damage That Good Can Inflict – The New York Times

What to know about the crisis in Haiti after the prime minister’s resignation – AXIOS