Mother Russia: The World of the Play

A Deep Dive on the Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union

By Emily Chackerian

“An Iron Curtain has descended across the continent”

The Cold War was a geopolitical conflict that lasted from the late 1940s to 1991 which saw the capitalist forces of the world (led by the United States, and largely represented by NATO) in direct opposition against the Communists (led by the Soviet Union, or USSR, and including the countries in the Warsaw Pact). The divide between these forces, referred to as the Iron Curtain, fell roughly between Western Europe (the Western Bloc), and Eastern Europe/Russia (the Eastern Bloc). While this ‘curtain’ is a use of poetic license from Winston Churchill, Germany played host to the Berlin Wall, which physically separated communist East Berlin from the Western side of the city.

Espionage, The Red Scare, and Dogs in Space

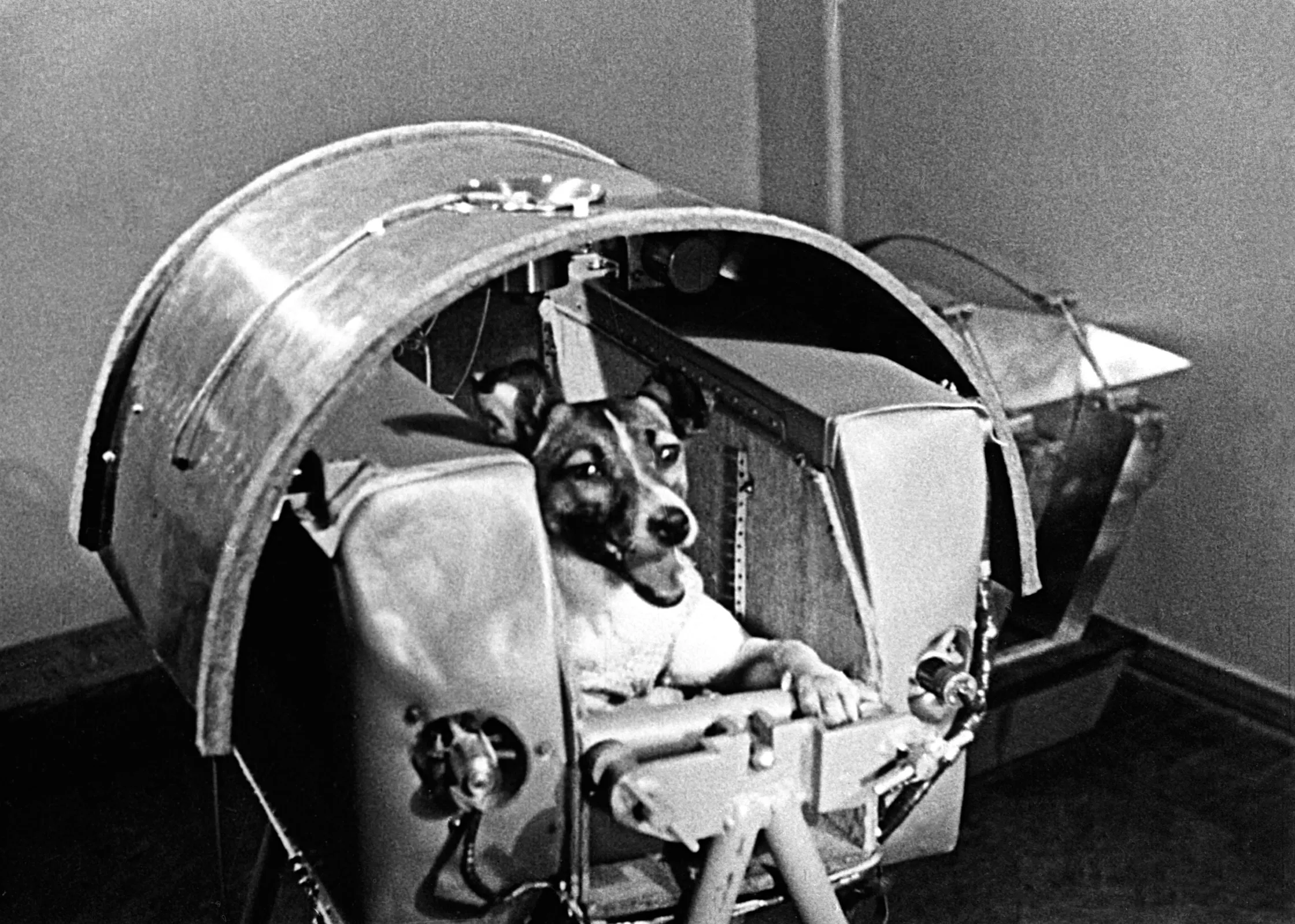

Although the Eastern and Western powers encouraged ‘proxy wars’ that were fought in other countries like North and South Korea, the Cold War was also significantly waged through ideology and information gathering. The US and USSR used intelligence gathering, political influence, nuclear technology, pop culture, and even the space race, each trying to wield more influence than the other. In the US, the early years of the Cold War brought about the second Red Scare and the rise of McCarthyism. Americans became paranoid and turned on the neighbors they believed to be Communists (this anti-Communist sentiment lasted into the 1980s). Meanwhile, Europe grew a vast network of spies while the USSR made new efforts to build their own nuclear weapons.

Mother Russia: Perestroika

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the Communist Party, and swiftly enacted policies known as glasnost and Perestroika. Glasnost, meaning ‘openness,’ was a move towards a more transparent government, while Perestroika (‘restructuring’) was an economic and political reform movement that aimed to bring about the end of the Era of Stagnation (which is, in fact, what it sounds like) by incorporating liberal economics.

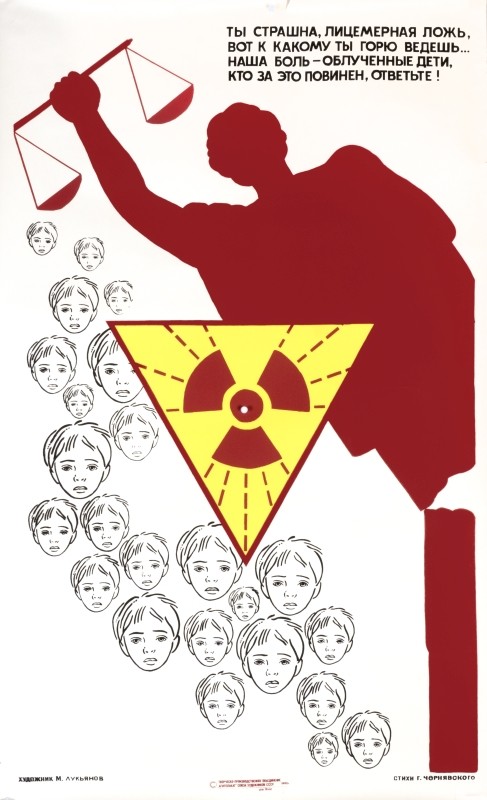

With both policies, Gorbachev hoped to promote free speech and information sharing. The policies succeeded in loosening censorship and price controls. In the pop culture sphere, the KGB-sanctioned Leningrad Rock club offered rock music and avant garde art a venue to thrive While it was simple to legalize rock music in the Soviet Union, there were limits to just how “open” Gorbachev’s government was willing to be. In 1986, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the Ukrainian SSR experienced an unprecedented nuclear disaster after a reactor exploded. While only 2 workers were killed in the explosion itself, over 200 people were hospitalized, and thousands of others experienced health complications from the radiation poisoning. The Soviet government chose not to warn the countless citizens who traveled to Chernobyl to help with disaster relief and were subsequently also exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. It is unclear if the government did not know the full scope of the disaster at the time or if they intentionally withheld information. The scope of the disaster proved to be unconcealable from the public, leading to widespread backlash and a distrust in Gorbachev’s new policies.

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Gorbachev credited the Chernobyl disaster as the most significant turning point for the Soviet Union, but it wasn’t the only one. His perestroika policy also encouraged the rise of nationalism within the Communist countries of the Warsaw Pact, and after roughly 40 years, these countries saw an opportunity to leave. In 1989, a wave of revolutions spread across Eastern Europe. One such shift in power was the Peaceful Revolution in Germany, during which the Berlin Wall was destroyed, reuniting Eastern and Western Germany, and offering a clear symbol of the fall of the Iron Curtain. Just weeks later at the Malta Summit between President George H. W. Bush and Gorbachev, the Cold War was declared officially over.

Two years later in Russia, Communist extremists attempted a coup to take the country from Gorbachev. The group opposed glasnost and perestroika, and credited the initiatives with the USSR’s rapidly decreasing power. While the coup failed, it did cost Gorbachev much of his influence and further elevated the status of new Russian President Boris Yeltsin. As the power of the USSR diminished, political crisis and civil unrest proved to be too much to handle, and on December 25, 1991, the Soviet parliament voted to dissolve the union.

The Wild Nineties

The end of communism brought significant change to Russia in the 1990s. Suddenly there was an influx of new products, new music, new ideology; capitalism was on the rise. At the same time, citizens’ savings were being devalued and the country experienced a drastic drop in gross domestic product. During this period, the planned economy was replaced by what historian Marshall Poe described as a “chaotic mix of banditry and capitalism.” Things had changed for Russia, and to its people, it didn’t necessarily seem like these changes had been for the better. And it is in this moment, these “wild nineties” where we meet Evgeny, Dmitri, Katya, and of course, our titular Mother Russia.

The cold war is all around us: Lasting Influences on Pop Culture

If you look for it, you’ll notice that references to the Cold War are everywhere in pop culture. Maybe this is because there’s always been a certain glamor to spies, maybe it’s because of Hollywood’s suspected entanglement with the Communist Party, or maybe it’s just a global conflict that lasted 40 years. So where can you find traces of the Cold War in pop culture?

- Theater:

- Mother Russia (Lauren Yee)

- Angels in America (Tony Kushner)

- The Baltimore Waltz (Paula Vogel)

- Chess (Tim Rice and Danny Strong)

- Cold War Choir Practice (Ro Reddick)

- Chaplin: The Musical (Christopher Curtis and Thomas Meehan)

- Vladimir (Erika Sheffer)

- Television:

- The Americans (FX)

- Slow Horses (AppleTV)

- Stranger Things (Netflix)

- Chernobyl (HBO)

- PONIES (Peacock)

- Literature:

- Cat’s Cradle (Kurt Vonnegut)

- Midnight in Chernobyl (Adam Higginbotham)

- Dr. Zhivago (Boris Pasternak)

- The Manchurian Candidate (Richard Condon)

- Film:

- The Lives of Others

- Tinker, Tailor, Solider, Spy

- Bridge of Spies

- The Hunt for Red October

- James Bond

- Dr. Strangelove

- The Third Man

Further Reading, Viewing, and Listening

- The MOTHER RUSSIA Mixtape

- Winds of Change

- McCartney: a Life in Lyrics – Back in the USSR

- The challenge of Chernobyl for Glasnost, Perestroika, and the stability of the Soviet Union

- Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia – PBS

- PBS Frontline: Comrades III: All that Jazz (1986)

- A Haven For Soviet Rock And Roll Is Long Gone But Its Music Still Resonates

- Red Wave: How Soviet rock made it to the US

Leningrad Rock Club photo in print display credit to Dmitri Konradt/NPR.